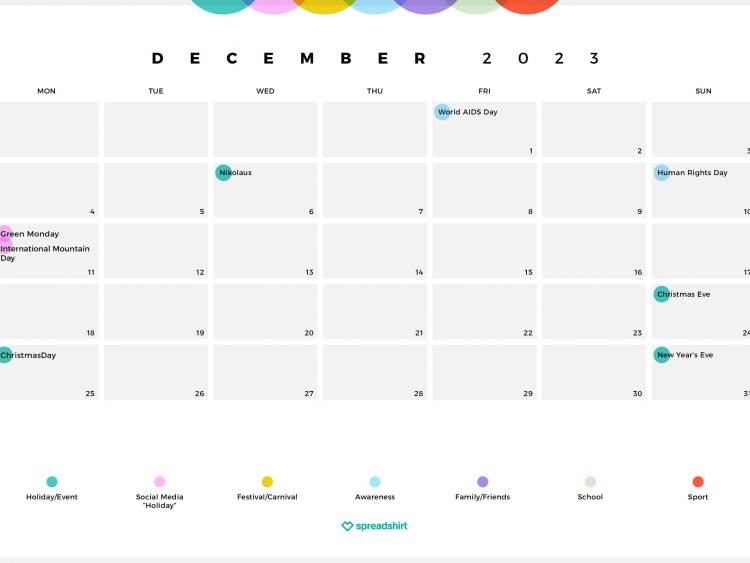

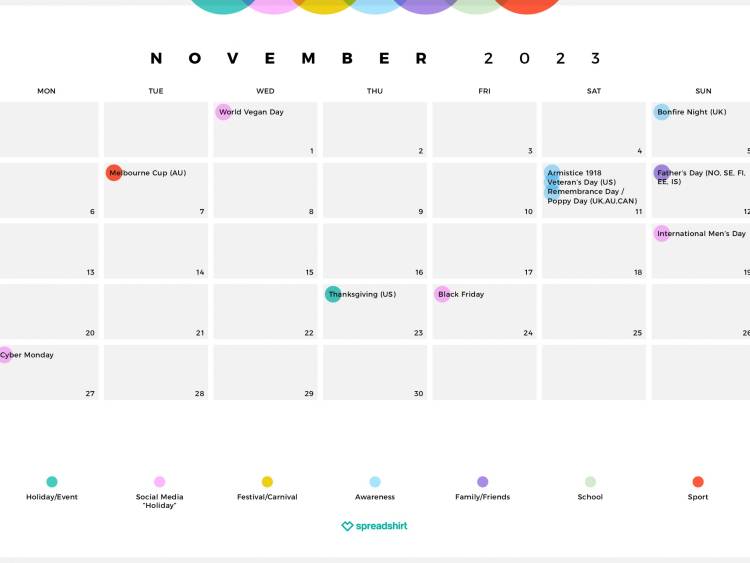

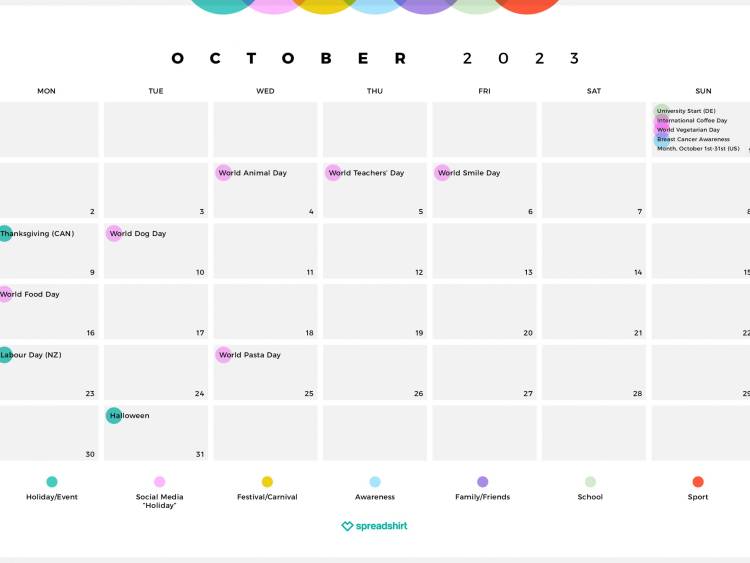

Most Important Occassions: October – December 2023

The fourth quarter of 2023 is upon us. But what do we have in store? You can find occasions to celebrate, remember and learn throughout this calendar. This little preselection of holidays is just waiting for your design ideas:

- International Coffee Day & International Vegetarian Day, October 1st

- World Animal Day

, October 4th

, October 4th - Canadian Thanksgiving, October 9th

- World Dog Day, October 10th

- World Vegan Day, November 1st

- International Men’s Day, November 19th

- Thanksgiving (US), November 23rd

- Black Friday, November 24th

- International Mountain Day, December 11th

- Christmas Day, December 25th

More exciting events are waiting for you in our calendar. Have a scroll through the next three months and discover suitable occasions for your designs.

Need some more drive to get you going? Our article on Top search terms October to December 2022 will be sure to put you on the right path.

Still have some burning questions? Get in touch with us on the Forum or in the comments section below.

The post Most Important Occassions: October – December 2023 appeared first on The US Spreadshirt Blog.

Looking for cool gifts? Check Rott515 store!

The cult of productivity

Is the decline of elitism of creativity inevitable?

Productivity vs. Creativity

“Do you think that the importance of creativity is declining?”

I recently posed this question to my wife. She spent most of her career in HR and doesn’t think about creativity or creative endeavors like I do. At the beginning of the pandemic, she left her cushy corporate job and decided to pursue being a life/career coach. Now as an independent professional, she creates way more content on various platforms than I do. Yet, she wouldn’t identify herself as a creative or a creator.

I’ve spent more than two decades as a creative. Quality over quantity has always been the mantra for us, the so-called Creative Class. Producing “less but better stuff” was what we were taught. Mediocrity, or settling for “good enough,” was the enemy. We worshiped the cult of perfectionism.

I’ve been sensing for a while now that, in the modern, technology-driven, and efficiency-obsessed society we live in today, we put less value on creativity and increasingly more on productivity. Producing “more but good enough stuff” seems to have become the new mantra.

Countless creators sing the gospel of consistency, frequency, and productivity.

In just the last 24 months, the number of self-proclaimed social media growth coaches and personal branding gurus seems to have exploded on Instagram, LinkedIn, and the platform formerly known as Twitter.

The pandemic accelerated this trend. While the cost of and the demand for elite colleges higher education didn’t get disrupted as much as some experts thought they would be, online courses' popularity rose significantly, from the elite end of the spectrum to the opposite end. Yet another way for Ivy League schools to make even more money.

In addition, many creators have now figured out how the algorithms of various platforms work. The platforms benefit when more people are posting more content more frequently. Creators desperate for irrational emotional affirmations in the form of followers and likes are willingly uploading stuff in masse and for free.

Furthermore, the format of content-i.e. Reels on Instagram-is now overshadowing the substance of content. Posts that tout “Use trending audio for your Reel and watch your account grow!” “Post _ times a week to gain more followers!” or those strangely quick and short clips that you have to watch and stop several times to see what’s going on proliferate the Explore feeds. We see numerous posts that have the same formats and techniques. Sure, they may have a large number of likes and followers but are they truly memorable? Probably not because there are so many.

These formulas are providing these creators with shortcuts for reach and growth. Everyone loves a good shortcut.

One thing that is common among them, however, is that only a fraction of them encourage people to be original or creative.

Put another way, algorithms of the online world are pushing creators and creatives towards quantity and formulas and away from quality or creativity.

The great thing about formulas is that they work, especially in the age of algorithms, while they work. The problem is that platforms and their algorithms are a moving target and change frequently and unpredictably. In a few years, 90% of these creators who chase formulas will either get tired of chasing them and/or algorithms will render them irrelevant.

Tools don’t make us smarter

The sense, or worry, I should admit, that productivity is overtaking creativity occurred to me as I was listening to a podcast in which the two hosts discuss the topic of productivity, and specifically, note-taking rather enthusiastically. This conversation fascinated me.

To begin with, I didn’t realize that there was a passionate cohort of note-taking aficionados out there. For Casey Newton-one of the hosts, a tech journalist who runs Platformer-note-taking is a professional obsession. He seems to organize his notes meticulously, and even mercilessly, and takes the task to a level that I never really thought about. He keeps a highly organized record of every link his articles on Platformer have referenced in Notion and uses a newly discovered note-taking tool called Capacities.io that helps “networked thoughts.”

His co-host, Kevin Roose, a technology columnist for the New York Times, is on the opposite end of the spectrum. His method, he reveals, is surprisingly low-tech for a tech journalist: emailing himself or taking voice notes in the Voice Memo app whenever ideas occur. He admits self-deprecatingly that his method, particularly the voice notes, makes searching for those ideas later almost impossible, ironically defeating the purpose of taking notes. He says he experimented with various note-taking tools, only to find himself getting frustrated with them 24 to 48 hours later and reverting to his archaic method of keeping a record of his ideas.

To be honest, I’m much closer to Roose than Newton on the spectrum of productivity savviness. For years, I’ve tried different means of taking notes/jotting ideas down/making to-do lists and I’m yet to find a system that I’m satisfied with. I did sign up for Capacities.io, opened it, but was immediately intimidated and went back to Notes.

While Newton advocates for productivity tools, he argues that note-taking apps don’t make us smarter in his article on Platformer.

In short, it is probably a mistake, in the end, to ask for software to improve our thinking. […] The reason, sadly, is that thinking takes place in your brain. And thinking is an active pursuit — one that often happens when you are spending long stretches of time staring into space, then writing a bit, and then staring into space a bit more. It’s here that the connections are made and the insights are formed. And it is a process that stubbornly resists automation.

Authenticity

I spoke at an event in Croatia last year and met Chris Do, the self-proclaimed “Loud Introvert, helping left-brainers, think right™.” On Instagram alone, he has close to a million followers, and on LinkedIn close to half a million. He’s a household name in the design community.

Although I didn’t get to know him directly until last year, I remember his firm Blind, a motion graphics company, more than a decade, if not two, ago in my twenties. Only a few years older than me and a designer like myself, I was very impressed with Chris running an Emmy-winning design company at a relatively young age. In the last decade, he shifted his work focus towards coaching and educating other designers to build businesses.

At a breakfast table of the event, we started chatting. My wife was with me and complimented Chris on his talk the day earlier. She mentioned how useful it was to her and wished that she could build her online presence more. He in return asked her what she did — a life career coach. When I bring my partner to an industry event where I’m speaking, people are usually more interested in talking to me. So it was rare and refreshing that a high-caliber speaker like Chris showed an interest in what my wife did.

The next question he asked her surprised both of us. “Can I help you?”

Here’s someone who has more than a million followers on social media, gets approached all the time for advice, and charges $5,000/hr for a 1-on-1 coaching session for personal branding. With this question, he wasn’t selling his service to her. He sounded genuinely interested in what my wife did and helping her on the spot. There was no agenda beyond that. It was authentic.

Creative and design industries are filled with big personalities and egos. In fact, regardless of the industry, anyone who is as successful and as well-known as Chris would have a big personality and be self-obsessed, and not be interested in talking about others.

Before meeting him, I admired Chris for his ability and tenacity to produce high-quality content on such frequency. During my two-decade-plus career, I don’t think I’ve ever met anyone who cared enough about a random stranger who wasn’t even in the same industry and offered to help. This personal encounter with him made me realize that it’s his authenticity that put him in a whole different class.

The long run

Towards the end of the podcast, Newton provides a few practical tips for staying organized and being productive. While he comments Reese’s basic use of technology is “horrible,” his last advice to his co-host is simple and refreshingly technology-independent.

“Keep a daily journal as a bullet list in the morning.”

In 2022, Drake supposedly released 57 or 58 tracks in one year alone. That’s more than one track a week. Even at his level of fame, when one’s descent from fame is as quick as someone else ascending and replacing them, he is savvy enough to understand that aiming for a stroke of genius every few years could be dangerous for his career. Instead, he is producing more in the Attention Economy we now live in to engage his audience more effectively, frequently, and consistently.

Statistically speaking, in baseball, a player who hits a single consistently has a higher chance of becoming a Hall of Famer than a player who becomes a home run winner in a few seasons.

It now seems that to be creative, we first need to produce more with consistency. Creatives need not be the hostage of quality, at least to begin with. While we should try to understand algorithms and need to produce more to stay relevant, that doesn’t mean we need to be subservient to algorithms. In fact, we should resist hacks, tricks, and gimmicks, to truly break away and stand out.

Sure, we can chase algorithms in an effort to grow our audience. In the long run, however, authenticity will prevail.

Thanks for reading. Add your notes with any feedback, thoughts, or questions. I’d love to hear from you.

Originally published at https://reiinamoto.substack.com.

The cult of productivity was originally published in UX Collective on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

Looking for cool gifts? Check Rott515 store!

When creatives quit

As creative managers, we take it personally when creatives quit. How should we cope?

When we quit

I don’t have a good track record of quitting or doing well when people on my team/at my company quit.

First, about my track record of quitting.

I didn’t last long in my first job. Fresh out of school and after having applied to several hundred positions over ten months in New York City, I finally got hired as a junior designer by a small but rapidly growing digital marketing agency. But after about 18 months, the agency that hired me got acquired, my boss left (or got pushed out, not sure), and overnight, the company that I had joined disappeared.

After that, my first steady job was at R/GA, a celebrated design and technology company in the special effects and computer graphics industry as it was transitioning into a digital creative and marketing agency. For the first two years, it was a revolving door of various bosses. The transition R/GA was going through was quite drastic. In hindsight, as a more mature-and perhaps slightly scarred-creative with perspectives on change, it made sense there was instability and high turnovers. For someone in their early/mid-twenties, however, it was disorienting. That led me to look for other jobs and I almost quit.

But then I couldn’t.

For those of us who are “legal aliens” (yes, an actual term used by the government) in the US on a visa, specifically an H-1B visa which is what I had, we are tied to the employer. For us to switch jobs, the new employer would have to agree to sponsor our visas. That process could take months and there was no guarantee that the visa would be granted. In my case, one company was willing to hire me until they realized that it would take too long.

I ended up staying at R/GA for over five years but didn’t officially have a boss there. That exposed me, for better or worse, to Bob Greenberg, the legendary founder and CEO of R/GA and the industry icon. With that, I inevitably got opportunities-or more accurately, had no choice but-to present work to and in front of him.

In his late fifties at the time, Bob had some heavy hitters as clients. Ian Schrager (the founder of Studio 54, Ian Schrager Hotels, and Edition Hotels), Richard Saul Wurman (the founder of TED), and Edwin Schlossberg (the husband of Caroline Kennedy), to name a few.

For such high-profile clients, projects I got to work on were similarly eclectic: a website for one of the hippest hotels in the world. An event opening title sequence for the most sought-after conference. A 50-story, multi-screen display for a building in the middle of Time Square. Though they could be challenging and intimidating for someone half their age, I got to do some diverse and interesting work.

The experience I got at R/GA during that era was invaluable. I consider myself a product of that company. Many designers and colleagues of my generation stayed there for a decade or more. Those who left became design and creative leaders of companies like Apple, Instagram, Google, and so forth. In a way, R/GA was the design nursery of Silicon Valley. It may have been good that I couldn’t quit in the first few years. The universe works in mysterious ways.

So why did I quit?

I mean, with those clients and diverse, interesting types of work I was doing, I was very happy.

There were a few reasons for me to move on at the time I did, though.

One, opportunities came knocking on my door. In my late twenties, I started to get phone calls and emails from headhunters of other agencies and that got me curious about what was outside the fences, literally as R/GA’s building in Hell’s Kitchen of NYC was surrounded by fences.

Second, I didn’t know if I was doing good work just because I was at R/GA or because I was actually any good. Am I just benefitting from the name and the team I’m on? Or am I making the team better? I wasn’t sure.

I decided to leave because I wanted to really test myself, challenge myself, and even make myself uncomfortable.

However, quitting R/GA didn’t go so smoothly. R/GA was the digital agency of record for Nike in the US. When I told people that I was going to AKQA, less prominent and not well known in the US at the time, their reactions ranged from “AK-what?” and “Why?” to “You are making a mistake.” AKQA was also working with Nike but in the UK and Asia. Someone even told me, “That’s like going from the Premier League to MLS.” Okay, the regions are mixed up in this metaphor, but if you know, you know.

One team was essentially stealing talent from another for the same client. This caused a lot of tension between the two agencies and a strain on the client. So much so that the client had to intervene and mediate a gentlemen’s agreement between the two to not poach talent from each other. This lasted for years.

I thought I’d try to give it five years at AKQA and see how things would turn out. I stayed for close to 11 years.

When others quit

Now about my track record of having creatives quit.

I did a little bit of hiring and managing creatives when I was at R/GA but it was at AKQA where I spent a significant amount of time recruiting, managing, leading, and very occasionally and unfortunately, letting people go.

Between 2005 and 2015, the agency grew tenfold organically. I went from managing a team of about 25 people in one office as an Executive Creative Director with another colleague, PJ Pereira, to representing hundreds of creatives across 14 offices around the world as the Global Chief Creative Officer. We became the first agency to receive five Agency of the Year accolades in a span of just a few years. By the time I left, AKQA was pushing 2,000 employees. I wouldn’t trade my experience there for anything else. I wouldn’t be doing what I’m doing now if it wasn’t for AKQA.

During my tenure, I reviewed probably more than 10,000 resumes and portfolios, interviewed hundreds of, if not over a thousand, people, and hired quite a few. I’ve seen numerous cycles of people coming and going.

When that cycle happens and people are about to quit, there are some tells.

When we used to see each other in person almost every day before COVID, some of those tells were more noticeable. So-and-so is gone in the middle of the day for no particular reason. Or they show up to the office late but rather well-dressed. In the post-pandemic, remote work world, those tells have become less visible.

But the lack of visibility is another kind of tell.

A turned-off Zoom camera, blocked calendar slots with no particular agenda, or people being oddly distant and disengaged on Slack, are such invisible tells. These then are followed by a “Can we have a chat/do you have a minute?” Slack message, or more commonly, a “Quick check-in” calendar invite that shows up on our calendar suddenly and randomly.

Geez, I sound like a f***ing creepy boss.

When I got into the position of hiring and managing people in my twenties, I wasn’t mature enough (note: I’m a man) and I didn’t know how to deal well with people quitting. Now in my forties, I’ve developed an occupational spider-sense. Even after more than 15 years, though, I still get a pit in my stomach when I see such a Slack message or a calendar invite pop up. I hate it when people quit.

We, as bosses to others, aren’t machines. We have feelings. Having someone quit can be an emotional process even if we put up a facade that might not seem so.

Here are a few coping mechanisms I’ve developed as a boss over the years.

1. Don’t react. Listen.

Regardless of the eventual outcome of someone staying or leaving, when one of our reports comes to us to have that “chat,” it’s natural to react on the spot. Even if we suppress our emotions on the surface, it hurts on the inside.

To compensate, we subconsciously end up talking more than we normally do. Maybe it’s just me. I’ve certainly caught myself talking more than the person who came to resign. In those cases, I almost always regretted later that I said too much or what I said.

That’s precisely when we need to hold back what we want to say and listen to what they say and don’t say. And even if we have things we think we should say, we need to wait at least overnight and digest it first.

Don’t react. Listen. Especially when we feel those emotions inside of us.

2. Counteroffers are useless (9 out of 10 times).

By the time one of our creatives comes to us to have the “chat,” it’s usually too late.

Earlier in my managerial career, I was told by a more experienced manager colleague that I should always try to counteroffer, especially if I wanted to keep them.

However, I’ve learned that if I convinced people to stay with financial incentives, they would end up leaving in six to twelve months. It was just a matter of time before someone else would offer more money than we could.

What felt even worse was that we made counteroffers and they would still leave. For these reasons, I stopped making counteroffers a long time ago. Competing with money, even more so now, is futile.

What we need to show people isn’t just more money. We need to show that we care about and value them. Sometimes, part of the reason for that “chat” is people subconsciously just want to know how much we value them.

So when is that one time we should make a counteroffer? It’s when we think we can cultivate a mutually beneficial path forward for the individual and the company. Be generous with the money within reason but more importantly, about their future with us.

3. Creatives are like flowers. They need the right amount of sunlight, water, and space.

This statement might rub some people the wrong way. But I used to be one of those flowers.

If I got some critical feedback about my work, I would take it personally and it would take me several days to come back to my normal self on the inside. If I didn’t get praised for my work or my work wasn’t chosen, I would feel insecure and worry that I wasn’t good enough. But too much praise would have made my head too big.

The thing about flowers is that they don’t tell us when or how much sunlight and water they need. It’s our job as a boss to approach the creatives, nurture them, and help them bloom. Don’t put it on them to come talk to us. Approach them ourselves and talk to them proactively and regularly, with enough space. Otherwise, they’ll suffocate.

4. If you love them, set them free.

Sometimes, we just have to accept the fact they want to move on for whatever reason.

If you love something, set it free. If it comes back, it’s yours. If not, it was never meant to be.

This quote applies to managing creatives but part of this quote that doesn’t apply is that they aren’t ours.

There are a few, not many, creatives that I’ve hired more than once. Many that have left, they’ve kept in touch with me-and I give them credit for keeping in touch-for many years, even after more than a decade. They’ve become my brothers and sisters, many younger, some similar age or older.

What’s ours to keep isn’t their employment. It’s the relationships. And it’s up to us, not them, to keep them.

A year after I left R/GA and joined AKQA (and before the aforementioned gentlemen’s agreement was in place), Bob called me and asked if I would be interested in returning. I said I wasn’t quite ready. Another year after that, he asked me if I would be available for lunch. Of course, I said. And just last year, he asked me if I could contribute to a side project he was working on. It had been 17 years since I left R/GA in 2005.

It’s nice to know that one of your old bosses still thinks of you almost two decades later.

The true character of a boss shows when one quits.

Thanks for reading.

Originally published at https://reiinamoto.substack.com.

When creatives quit was originally published in UX Collective on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

Looking for cool gifts? Check Rott515 store!

Seven traits of a good boss

There is no such thing as a perfect boss but these seven traits might help identify the good ones

The first boss

The first boss I ever had in the creative industry was Noriyuki Tanaka, a legendary artist/designer in Japan in the 1990s. I managed to get an apprenticeship position at his studio as I was about to graduate from college through an acquaintance who made an introduction to him for me.

Not even 40 yet, Noriyuki-san was a prolific star designer/artist who was producing an eclectic body of creative work. He did client work to earn money and would use that money to create his own artwork and organize art shows. His approach to creativity was pure, ambitious, yet practical all at the same time.

To this day, the experience I got under him remains the most intense one I ever had in my 20+ career.

After I left his studio, his stardom became even more stellar. He created the first TV spot for Nike in Japan in the 1990s. Later, he became the first creative director for Uniqlo and helped make it a major apparel player in Japan well before it became the internationally recognized brand that it is today.

He was the best and possibly the trickiest first boss to work for.

I say this with the utmost respect and a lot of love. I told him as much when I saw him a few years ago over sushi in Tokyo.

He was the best because his pursuit of creativity was relentless. Until I worked for him, I didn’t know how one would earn a living by being creative. He may not be well known outside of Japan, but his work was world-class and some of the most creative and artistic work I’ve ever seen. Without his tutelage, I wouldn’t be here. Period.

When I now tell people in the industry in Japan that I worked under Noriyuki-san, they all get impressed, even 25 years after the fact. He’s one of the very few people I know directly for whom the word “genius” is used. He was and still is a man of legends.

And that’s often followed by “Did he ever show up on time?” He was notorious for not being punctual. Another one of many legendary tales of Noriyuki-san.

He had very little if any, grasp of time. He was so bad about managing the time that it was completely unpredictable what time he would show up. Being late three hours to a meeting was the norm. Japan, as some readers might know, is a painfully punctual society where a minister was forced to apologize because he was three minutes late to a meeting, or a train company delivered a formal apology because one of its trains left a station just 20 seconds too early.

Even with his lack of punctuality, he still kept his clients. Noriyuki-san was that good.

His studio was just him and his art director/designer. I joined as a very inadequate third leg of the stool. There was no job description for the position because, well, it wouldn’t have mattered anyway.

My job included anything and everything. My day started with cleaning the bathroom, sweeping the floors, taking the trash and heaps of cigarettes out (the studio had no cleaning service), answering emails and phone calls, scheduling meetings (a tricky endeavor, see above), delivering disks to the vendor (the Internet wasn’t fast enough to handle heavy files), bringing printed work back to the studio before we showed them to clients, etc. In between these, I asked for bits and pieces of design work that I could get from my superior art director and tried to touch as much of the studio’s work as possible.

In the 1970s and 80s, the Japanese word “karoshi (overwork death)” became known outside of Japan. The corporate culture in the 1990s when I started working there hadn’t drastically improved.

This, coupled with Noriyuki-san’s lack of time management, made my working hours just insane. The day would start around 11am and it would continue until about 6am the next morning (yes, 19-hour day). I would go home to take a shower, doze off for a couple of hours, and then be back at the studio around 11am the next day. This happened 4 or 5 days out of the 6 days a week that I worked. It was a brutal introduction to the creative industry.

It sounds horrible, I know. Still, I now appreciate the exposure to the level of creativity from my first boss at the very beginning of my career.

“I had to clean up my act,” said Noriyuki-san with a shrug over drinks after that sushi dinner. He told me he got his lifestyle in order, now manages his time better, quit smoking, and started eating much more healthily. Granted, this was around 1am, so maybe not the healthiest but it’s all relative. Regardless, he looks remarkably young for someone who is over 60.

Seven traits

Since Noriyuki-san, I’ve had several bosses, as one would, over the course of my 25-year career. If I were honest, not every boss was great, but that’s ok, there is no such thing as a perfect boss. I learned something from everyone.

Here are the traits that I observed and valued from various bosses. Combined, they might give us an idea of what we should look for in a boss.

1. Motivate

Although not the easiest job, what I appreciated about working under Noriyuki-san was, in addition to his relentless appetite for never-been-done ideas, his way of motivating us that I grew to appreciate, even years after I had left his studio.

In the early days of my apprenticeship, I remember him telling me, upon showing my work, “You have something better in you. Why don’t you iterate and find it?”

Much like a good coach who can make us a better player, a good boss pushes, not forces, us to a new height that we didn’t reach on our own. They can motivate and elevate us beyond our abilities.

2. Have a superpower

Every boss that I respected, even if they might have been flawed, had some kind of superpower.

One knew how to tell a story. Really well.

Another had such magnetic and infectious energy around clients that made them enamored and naturally want to work with us.

One designer boss I knew had such a strong command of keyboard shortcuts of design software that watching him design was like watching someone playing the piano.

David Ogilvy, one of the advertising tycoons of the 20th century, recalled his days working in the kitchen of the Hotel Majestic in Paris and said that whenever the executive chef picked up the knife to cook, everyone in the kitchen was in awe of the master at work.

A good boss has some superpower that we aspire to.

3. Take action

“What do you think we should do differently at this company?” One Japanese CEO that I work with asked me out of the blue a few years ago. I told him that they needed more females in the position of power. A year later, the CEO named a female leader as a regional CEO. It might not sound like a big step but in a male-dominated corporate culture of Japan, this was a rarity and I was impressed by the fact he took action.

4. Have our back

Back in 2002, an employee suggested to Tadashi Yanai, the global CEO of UNIQLO and its parent company Fast Retailing, that they start a grocery business selling fruits and vegetables. The logic was that UNIQLO had such a strong understanding of supply chain management that they could apply the know-how to the distribution of fresh produce and eliminate waste.

All the board members were against it, but Yanai was not. “Try it.”

Less than two years later, UNIQLO lost more than 30 billion yen (≈$20 million) and decided to halt the venture. Feeling accountable for the failure, the employee gave a resignation letter to Yanai.

“What are you talking about? Use the experience for the next time and earn back the money we lost,” said Yanai to the employee with a laugh.

This employee was Osamu Yunoki who later started GU, a younger sibling brand to UNIQLO, and made it the second biggest brand within Fast Retailing. Yunoki is the CEO of GU.

When a boss has our back, it could be more empowering than one would ever imagine.

5. Listen to our needs

Tom Bedecarre, the former CEO of AKQA, was the person who hired me back in 2004. At the time, AKQA was virtually unknown within the industry. I thought I would give it a try for a few years and see what would happen. I ended up staying there for more than a decade.

Throughout that time, Tom would always ask me what I wanted to do and accomplish. At times I had some clear goals and desires, other times, not so. What Tom did was always listen and gave me different opportunities. This meant that I was able to have multiple roles and grew in ways I didn’t imagine I could.

6. Care about us

In my early twenties, I had an accident while playing soccer after work and lost my eyesight in one of my eyes. It was a retinal detachment and a few other complications that required multiple surgeries.

Bog Greenberg, the founder and CEO of R/GA, heard about my injury a few days after the incident. He made a point of coming to my desk to bring a yellow sticky note with a phone number on it.

“I just talked to one of the best eye doctors in the country about your injury. He’s in New York. Call this number now,” said Bob.

I dialed and talked to Dr. Stanley Chang and got to see him right away. In addition, Bob gave me a check for $6,000 or 7,000 to cover the deductible that I had to pay to the insurance company for my surgery.

I’m forever grateful for the level of care Bob gave to me.

7. Admit mistakes

“I am sorry” are the three most difficult words for bosses to say, especially male ones. But when a boss is man enough to admit their mistake(s) and actually apologizes, that can be a powerful means of connection.

Many years ago, an old boss of mine apologized to me after a rather unpleasant exchange we had. He was sincere, which made such a positive impression on me that my level of respect increased quite a bit after that. That incident made me trust him more.

Writing these now, I realize that I’ve been fortunate enough to have some amazing bosses. That now makes me want to try harder to be a better boss to the people around me. I hope I can make a fraction of the difference for them that my former bosses made for me.

There are many more bosses I’ve had over the years that I didn’t have room here to mention. Every one of them made an impact on me and I’m one way or another a product of their influence. I hope to see them in person one day again and tell them how much their mentorship meant to me.

Thanks for reading. If you like what you read, please subscribe and get my newsletter, every week directly in your inbox.

Originally published at https://reiinamoto.substack.com.

Seven traits of a good boss was originally published in UX Collective on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

Looking for cool gifts? Check Rott515 store!

Call for Artist Ambassadors: Help shape the future of Redbubble

Looking for cool gifts? Check Rott515 store!

Race to the top

To stay relevant in an age of automation, we need to move upstream, not downstream.

“I am an AI designer.”

When I was in high school and college, I devoured printed graphic design materials.

They were album covers from labels like Factory Records, posters for artists like Bjork, and magazines like Ray Gun, Emigre, and Japanese publications such as Idea. I admired star graphic designers and design studios like David Carson, Peter Saville, tomato, and the Attik. In design competitions, annual reports made regular appearances. As I couldn’t yet afford expensive design books, I used to spend hours in the university library and the art section of bookstores.

I thought I would follow the path of becoming a graphic designer in the traditional sense.

While I was in college, the Internet, or the World Wide Web, almost overnight, became a thing that people got obsessed about, much like AI today. After graduating, I moved to NYC, where the web industry was rapidly growing. “Web design” suddenly became an option for designers, at least as a career entry point for me.

“Tell the landlord you are a web designer, not a graphic designer.”

That was the piece of advice I got when I was looking for an apartment. That’s how much the Internet economy was starting to boom. I borrowed money from my parents to last for a few months and lived in a tiny one-bedroom apartment with my twin brother in a sketchy neighborhood in Brooklyn. We only got the apartment not because I was a web designer (I wasn’t as I didn’t have a job) but because the Albanian landlord took pity on us two young Japanese guys trying to make it in NYC.

Every week, I would look up job listings in a magazine called Silicon Alley Reporter and started applying for numerous design jobs and roles.

The combination of being fresh out of school, new to the City, and with no connection was a hurdle to begin with. Add “need H1-B visa” to that mix, no employer was willing to take a chance on a designer with no experience. I made ends meet by taking on random freelance web design gigs, like designing and coding web articles for $150/piece. I could barely get by.

Even with the “web designer” title on my resume, no company would still hire me. With a lot of time on my hands for many months, I reworked my printed portfolio into an interactive online portfolio. I had double-majored in art and computer science in college and knew a little about programming languages like C, C++, and Java. In addition to traditional design and art pieces, I had a few interactive typographic pieces, inspired by another role model of mine John Maeda who had told me to learn programming a few years prior.

It wasn’t the fact that I claimed to be a web designer that helped me land a job. It was my design taste mixed with technical skills that ended up differentiating me as a designer. My book wasn’t necessarily better than other designers. It was different.

If you tell your prospective landlord today that you are a web designer, your application will likely be denied. In recent years, landlords in NYC might be favoring job titles like “digital product designer.” In 2023, “prompt designer” or “AI designer” might give you a better chance.

“The term ‘AI artist’ irks me,” I heard an artist grumble recently. “If you are asking AI to do the work for you, you aren’t really an artist.”

While I can sympathize with this artist’s sentiment, it won’t stop the wave of AI as well as a whole lot of mediocrity from being generated.

A cautionary tale

Speaking of AI and people revolting against technology, there are several analogous cases from the past. One such case is elevator buttons.

It was in 1892 when the first elevator buttons were invented and introduced. Until then, elevators needed trained human operators to function. This invention made it possible for passengers to just press a button and be taken to the desired floor.

“So what happened to elevator operators? Nothing.”

Kevin Roose, a NY Times technology columnist, mentioned this story on the podcast “Hard Fork” a few weeks ago, referring to the wave of automated elevators that people thought would take over their jobs. That week, he was attending the Cannes Lions Festival of Creativity where he heard an abundance of talks and mentions of AI but in actuality, he didn’t observe innovative or revolutionary use of AI. The point Roose was trying to make with the elevator story was that it might take longer for AI to take over human labor and tasks than we currently anticipate.

In reality, it took a long time for elevator buttons to become common. Over 50 years in fact.

Throughout the first half of the 20th century, elevators remained human-operated. The core issue in automated elevators was mistrust. Humans just didn’t feel safe in elevators without other humans operating them.

From the 1920s to the 1960s, there were several strikes, notably in New York, Philadelphia, and Chicago, by elevator operators mainly protesting low wages and brutally long working hours. The irony of these strikes is that they became the catalyst that sped up elevator automation.

The strikes forced elevator manufacturers to think of ways to make riders feel safe. In the few years following a massive strike in 1945 in New York City that cost an estimated $100 million in economic loss to the City, companies started to introduce human interface elements within elevators that would provide a better sense of safety: emergency stop buttons, embedded phoneµ to let the riders talk to remote operators, and alarms were such safety measures.

Finally, in 1950, the first operatorless elevator was installed at the Atlantic Refining Building in Dallas. That marked the beginning of the end of elevator operators. “By the 1970s most elevators operated without human operators,” writes Henry Lawson Greenidge in his article “ How A Historic Strike Paved the Way for the Automated Elevator.” Resistance proved to be futile.

This may be a cautionary tale for the Writer Guild of America.

More with less

“I have to work much harder now.”

A seasoned photographer friend of mine lamented over afternoon coffee a few years ago.

In his fifties, he has been a still-life photographer in New York City for over 30 years. His expertise is shooting cosmetics products for major brands like Estée Lauder, Shiseido, Clinique, and MAC, among others, and his work has graced many magazine pages, posters, and billboards. Each photo he takes is carefully crafted, curated, and choreographed. In his field, he is established enough that he could command, I speculate, five figures relatively easily. If he does one or two of those assignments a month, he could earn a comfortable living even in an expensive city like New York City. From what I could gather, he’s done alright.

“I used to spend an entire day setting up one shot. Now I have to do ten shots a day.”

For a similar kind of fee, he says his clients nowadays demand much more work from him.

During his career, he has seen a dramatic evolution in technology. He is old enough to have started his career in the days of film. I’m also old enough to have learned film photography when I was in high school. We could shoot only up to 36 photos on one roll of film. We would develop film and print photos in the darkroom, and the process would take hours if not overnight.

This process now requires no discernible skill, talent, or special equipment. It barely takes milliseconds, if that. And it produces exponentially more volume. In 2023, over 85% of all photos are now taken on smartphones.

With generative AI, we don’t even need a camera or a smartphone to shoot. We can just… generate.

Soon, my photographer friend could be asked to do a hundred shots, if not more, a day for less money.

Or, he may not even be asked at all. If he’s in a race to the bottom, that is.

Creativity is the only job left

Obviously and admittedly, being an elevator operator and being a creative are drastically different professions.

Just as getting on an elevator without a human operator was unthinkable, automatically generating sentences and images were unfathomable before generative AI. Now, just with a few keystrokes, we can generate.

Nike’s mission statement reads “If you have a body, you are an athlete.” The same idea could apply to creativity: if you can type, you can be a creative.

Throughout history, technology democratized creativity. Cameras allowed people to create realistic images without being a skilled painter. Vinyl gave DJs new ways to make music. Smartphones made everyone a decent photographer. Squarespace didn’t make everyone a web designer but it did give access to good-enough web design for everyone for free.

While technology de-industrializes creative professions, it forces creative professionals to adapt.

David Lee, the Chief Creative Officer of Squarespace and an old friend of mine, made a few points that I thought are useful in framing how humanity can thrive in an age of machine automation.

1. Designers and creatives, move upstream.

My photographer friend, instead of trying to shoot more shots per day, changed his methodologies as well as outputs. He decided to move upstream and now directs product photography and videography for cosmetics as well as technology hardware companies by leveraging his experience. He’s now incorporating AI into his process.

Move upstream, not downstream.

2. Taste is the new skill

Anything that can be repeated is going to be automated by machines. If we are doing the same task day in and day out, we need to watch out.

The phrase “Taste is the new skill” is from the digital artist Claire Silver. “With the rise of AI, for the first time, the barrier of skill is swept away.”

Taste was always the skill creatives needed to have to succeed. As David put it, what’s old is new again.

The aforementioned photographer, with years of experience and training, has better taste and better creative judgment than those without. His taste is the differentiator.

3. Creativity is the only job left

Making the work used to be a big part of creativity. That may be changing slightly. As the barrier to entry for making creative things gets lower, there will be more premium on ideas. Those who can come up with original thoughts will continue to be the ones to thrive in an age of machines.

And that requires a race to the top, not to the bottom.

To listen to my conversation with David Lee, please take a listen here:

Apple Podcast: https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/thriving-in-an-age-of-automation/id1669660940?i=1000622567070

Spotify: https://open.spotify.com/episode/70iEWujVum92KesRYZQJIU

If you like what you read, please subscribe for my weekly newsletter at https://reiinamoto.substack.com.

Thanks for reading.

– rei ★

Originally published at https://reiinamoto.substack.com.

Race to the top was originally published in UX Collective on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

Looking for cool gifts? Check Rott515 store!

Design Through the Decades: 90s Style

Ready to take a journey back to the most contradictory and creative decade of all time? The 90s called and want their fashion back – so we’re going on a little trip to find the origins of so many of the styles that are having a resurgence today.

Millennials spent their youth – or at least their childhood – in the 1990s. This decade was formative for many adults today, and it a was a wild time when subcultures rolled together into one amorphous, sometimes contradictory ball of loud noises and bright colors; Pop culture with a capital P. Grunge, rave, hip-hop, punk, goth and the most dazzling pop stars imaginable; the 90s had something for everyone.

The trends of the 90s were reflected in the spaces of music, fashion, television, and incredible toys (Tamagotchi says hi). We get all sentimental at the thought of baggy jeans, crop tops, flannel shirts, and tie-dye. But styles also clashed in the world of design; the grunge aesthetic of Nirvana came up against the pink bubblegum pop of Britney Spears, creating a new space for experimentation and style-conscious rule-breaking.

If you know every word to the songs of the Lion King and bawled your eyes out when Jack went down with the Titanic, you’ve come to the right place. For all you nostalgic 90s babies out there, we’ve rounded up some of the biggest design trends of the decade.

Pop culture

Butterfly clips and lip smackers, Friends and the Spice Girls, the 90s was a decade filled with unforgettable pop culture moments – something that filtered through almost every aspect of fashion, music, movies, decoration, and design. We were all BFFs with Rachel and Phoebe, incredible dance moves were born, and fast food was suddenly high on the menu. Although the 90s ended more than 20 years ago, some of these icons are (thankfully) still making waves today. Many of these trends have made a glorious comeback in recent years, with brands, artists, and designers specifically tapping into the nostalgia of millennials, now that they have real jobs and some sort of disposable income. Some of the world’s biggest brands have begun to incorporate the pop culture elements of the 1990s into their advertising, experimenting with iconic design styles such and grunge, Memphis style, and anti-design.

A brief history in designs

The beginning of the 90s was initially characterized by the trends of the 80s, such as the Memphis style. The rest of the decade was mainly led by technological progress, which offered designers almost unlimited possibilities for expression. This led to the fact that in the 90s there was not just one unified movement in style, but many different directions. So many, in fact, that a counter-movement to the very concept of cohesive style emerged in the anti-design movement, in which design rules were consciously ignored.

The style of the 1990s was a colorful mix of different influences that reflected cultural and technological change. Grunge and minimalism emerged and embodied rebellious aesthetics in their own ways, one by subverting the aesthetic consumerism of mainstream pop and the other by rejecting its excess and loud palette. Pop culture references and bold colors were popular, while techno-futurism embraced the digital age. Typography experimented with unconventional approaches. Gradients, patterns and a DIY ethos added depth and individuality, and thanks to their openness, the designs of the 90s permanently changed the visual landscape.

Backstreet’s back: 90s design comebacks

Grunge

The grunge movement emerged in the early 90s and had a huge influence on fashion and design. It was characterized by its rebellious and non-conformist attitude, reflected in its casual, second-hand style. Flannel shirts, ripped jeans, and band tees were inspired by famous style icons like Kurt Cobain.

Layouts without grids, the aesthetic of torn and shredded paper or other used materials, and the scanning and deforming of structures and textures are typical of grunge. The mix of analog and digital design elements is characteristic of this dynamic style.

Minimalism

While grunge represented a more relaxed and raw aesthetic, minimalism developed as another alternative to pink, shiny popstars. It emphasized simplicity, clean lines, and a pared-back approach. Minimalist design was often characterized by monochromatic color schemes, geometric shapes, and a focus on functionality.

Pop culture

The pop culture-influenced design styles of the 1990s were a vibrant and mashed-together fusion of various influences. Nostalgia was celebrated and popular icons and references found their way into design. Elements from movies, television shows, video games and comics became central motifs that appealed to the interests and memories of different subcultures and generations.

Bold and bright colors, neon hues, and rich color palettes dominated the design landscape. Typography took on experimental traits, playing with proportions, distortions, and mixed fonts. Gradients, patterns, and DIY aesthetics gave designs a playful and dynamic feel. The pop culture design style of the 90s left a lasting impressing and became the particular dominant expression the period.

Techno-futurism

The style of techno-futurism in the 1990s reflected the enthusiasm and fascination for the emerging digital age. It was characterized by a sleek, futuristic aesthetic inspired by technology and science fiction. Metallic finishes, neon colors, and digitally inspired graphics were key elements. The color palette included bold and contrasting tones that conveyed a sense of energy and innovation.

Typography experimented with unconventional and innovative approaches. Color gradients, patterns, and slender geometric shapes added depth and dimension to the designs. The techno-futuristic style of the 90s was characterized by its typical dynamic aesthetic, which explicitly welcomed technological progress.

Bold & vivid colors

Bright, bold colors were a trademark of the 90s. They brought a sense of energy, excitement and individuality to various areas of design, including fashion, graphics and interior design.

Petrol, magenta, neon green, electric blue, and other saturated hues dominated the color palettes of the time. These colors were often used in contrasting combinations, creating eye-catching compositions. Neon colors and fluorescent tones became increasingly popular and were found in everything from clothing to advertising.

The daring color choices of the 1990s reflected the cultural change and lifestyle of the time. They conveyed a sense of rebellion, non-conformism, and a desire to stand out. These bright colors were picked up by the various design movements such as techno-futurism and pop culture inspired aesthetics.

The bold and bright colors of the 90s made a statement wherever they were used. They conveyed a sense of fun and playfulness, broke the boundaries of traditional color schemes and invited experimentation. To this day, they awaken a longing for the lively spirit of that decade.

Find more inspiration here: Pinterest 90s color palette

Experimental typography

The typographic experiments of the 1990s broke with traditional rules and pushed the boundaries of typography that had been common until then. Designers used distorted and deconstructed letterforms, mixed different typefaces, and experimented with scale and spacing.

Hand-drawn elements and a collage-like aesthetic became popular. Collage techniques, cut-and-paste elements, and a layering of text added depth and meaning to typographic compositions. Designers challenged the status quo, pushing the limits of legibility with their typefaces and thus expanding visual communication. These experiments continue to influence design practice today and emphasize the creative freedom of typography.

Color gradients and patterns

In the 1990s, color gradients and patterns were important design elements that added a special visual touch to creative media. Designers used color gradients to create depth and dynamics, while patterns provided playful and decorative accents.

Strong contrasting colors were often used, flowing into each other. They stood for energy and embodied the dynamic spirit of the time.

Patterns were another important element, adding a playful and decorative touch to the various designs. Polka dots, checkerboard patterns, squiggles and abstract shapes provided structure and rhythm, often in bright color.

The combination of these elements created eye-catching and exciting designs that celebrated the individuality and creativity of the time. This aesthetic continues to inspire contemporary designers to add depth and movement to their creations.

Dive in: inspiration and tutorials

Practice makes perfect! These tutorials will show you how to master the designs, patterns, and lettering of the 90s, and let you incorporate 90s design innovation into your own creations.

- https://creativecloud.adobe.com/de/discover/article/must-love-the-90s

- https://design.tutsplus.com/articles/90s-graphic-design-trends-from-aesthetic-fonts-grunge-patterns-and-rave-flyers–cms-35224

- https://reallygooddesigns.com/90s-graphic-design/

- https://stock.adobe.com/de/search?k=90s%20patterns

- https://design.tutsplus.com/tutorials/how-to-make-90s-geometric-pattern-using-basic-shape–cms-29334

- https://www.vandelaydesign.com/90s-patterns/

- https://www.designyourway.net/blog/90s-fonts/

Can’t get enough of the 90s? Our Pinterest mood board has enough inspo to keep you satisfied.

Thirsting for more of that sweet, sweet nostalgia? We’ve put together the most important and influential vintage style in one fun little article.

The post Design Through the Decades: 90s Style appeared first on The US Spreadshirt Blog.

Looking for cool gifts? Check Rott515 store!

In-Depth Guide to Vintage Design

In the dynamic world of fashion, some styles possess an ageless allure that transcends time. Vintage designs, with their nostalgic charm and timeless appeal, have the power to captivate hearts across generations. As a t-shirt company, embracing vintage styles opens up a world of creative possibilities, allowing designers to craft unique and captivating garments. In this article, we delve into the essence of vintage design, exploring its history, diverse styles, and offering valuable tips to inspire designers on their journey of experimentation.

What is Vintage Design?

Vintage design refers to aesthetics and styles inspired by past eras, typically from the early 20th century to the late 1980s. It celebrates the rich cultural heritage of bygone times, infusing modern creations with the spirit of yesteryears. Vintage designs often evoke feelings of nostalgia, taking us on a journey down memory lane.

Vintage in One Word: Nostalgia

At its core, vintage design is synonymous with nostalgia. It taps into our collective memories, reminding us of simpler times and cherished moments. Whether it’s the elegant flair of the Roaring Twenties or the rebellious spirit of the punk era, vintage styles transport us back in time, evoking a sense of sentimentality that resonates deeply.

Retro vs. Vintage

While the terms “retro” and “vintage” are often used interchangeably, they hold distinct meanings. Retro refers to contemporary imitations or revivals of past styles, while vintage denotes authentic designs from the past. Vintage designs are the genuine articles from the era they represent, carrying historical significance and cultural value.

Short History of Vintage

The concept of vintage design gained prominence in the 20th century as a reaction to rapid industrialization and mass production. As people sought a connection to their past, they began appreciating and preserving older styles and artifacts. Today, vintage design continues to thrive, captivating designers and fashion enthusiasts alike

Vintage Styles

1. Victoriana

Inspired by the opulence and refinement of the Victorian era, the Victoriana style transports us to a time of elegance and romance. Delicate lace, high collars, and intricate details define this aesthetic, capturing the essence of Victorian fashion. T-shirts designed with a Victoriana touch often feature vintage-inspired illustrations of Victorian women in their flowing gowns, surrounded by floral motifs and ornate frames. The use of soft, muted colors, such as pastel blues, pinks, and creams, further enhances the vintage allure. The Victoriana style’s enduring appeal lies in its ability to evoke a sense of grace and sophistication, making it a perfect choice for those seeking a touch of timeless beauty in their wardrobe.

2. Gothic

Taking inspiration from Gothic architecture and literature, the Gothic vintage style embraces a dark and mysterious aesthetic. Black is the predominant color, symbolizing the darkness and depth of the Gothic world. Designs often incorporate intricate patterns, such as ornate ironwork or medieval-inspired motifs, evoking a sense of ancient mystique. Gothic-themed t-shirts may feature iconic elements like ravens, candelabras, and gargoyles, adding a touch of darkness and enigma. This style’s allure lies in its ability to appeal to those with a taste for the macabre and those who appreciate the artistic and poetic beauty that lies within the shadows.

3. Letter Press

Rooted in the art of letterpress printing, this vintage style captures the essence of a bygone era when printing was a meticulous craft. T-shirts designed in the letterpress style often feature vintage typography, reminiscent of old typewriter fonts or classic book printing. The texture of letterpress printing, with its slightly raised ink impressions, is often mimicked in these designs, giving them a tactile and authentic feel. The color palette tends to be earthy and subdued, exuding a sense of warmth and craftsmanship. This style’s appeal lies in its ability to infuse contemporary designs with a touch of history, appealing to both design enthusiasts and those who appreciate the art of traditional craftsmanship.

4. Art Nouveau

Known for its flowing lines and nature-inspired motifs, Art Nouveau is an iconic vintage style that captivated the late 19th and early 20th centuries. T-shirts designed in the Art Nouveau style often showcase sinuous curves, floral patterns, and elegant female figures, paying homage to the era’s fascination with nature and feminine beauty. The color palette typically includes soft pastels and natural hues, reflecting the gentle, organic aesthetic of the style. Art Nouveau designs possess a mesmerizing quality that enchants viewers with their harmonious and graceful compositions, making them a perfect choice for those who seek an artistic and sophisticated vintage touch in their attire.

5. Art Deco

Embodying the opulence and extravagance of the Roaring Twenties, Art Deco is an influential vintage style known for its geometric shapes and lavish ornamentation. T-shirts designed in the Art Deco style often feature bold, angular patterns, intricate detailing, and stylized depictions of animals, sunbursts, and skyscrapers. The color palette is rich and luxurious, incorporating metallics like gold and silver, along with vibrant jewel tones. Art Deco designs exude a sense of glamour, celebrating the spirit of the Jazz Age and the roaring twenties, making them a favorite among those who appreciate the exuberant and celebratory vibe of the time.

6. Bauhaus

Rooted in the principles of functionality and minimalism, the Bauhaus style is a testament to the early 20th-century modernist movement. T-shirts designed in the Bauhaus style often feature clean lines, simple geometric shapes, and a focus on form and function. The color palette is typically limited to primary colors and neutral tones, reflecting the Bauhaus movement’s emphasis on simplicity. Bauhaus designs exude a sense of order and efficiency, appealing to those with a taste for clean, contemporary aesthetics, while also offering a nod to the avant-garde pioneers of modern design.

7. Mid-century pop-art

Drawing inspiration from the mid-20th century, Mid-Century Pop-Art is a vintage style characterized by its bold and vibrant imagery. T-shirts designed in this style often feature bright colors, graphic patterns, and pop culture references from the era. Elements like retro advertisements, comic book-style illustrations, and iconic symbols from the 1950s and 1960s are popular choices for these designs. The Mid-Century Pop-Art style’s appeal lies in its ability to evoke a sense of fun, nostalgia, and playfulness, making it a favorite among those who appreciate the exuberance and optimism of the mid-century era.

8. Punk

Born in the 1970s as a rebellion against mainstream culture, punk style embodies a raw and DIY attitude. T-shirts designed in the punk style often feature edgy graphics, distressed elements, and bold, rebellious messages. The color palette is dark and grungy, with black, red, and metallic accents dominating the designs. Punk-inspired t-shirts embrace an anarchic spirit, appealing to those who march to the beat of their own drum and seek to make a bold statement with their attire.

9. Steampunk

Merging Victorian elegance with industrial elements, steampunk is a fantastical vintage style that imagines an alternate reality where steam-powered machinery thrives. T-shirts designed in the steampunk style often showcase intricate gears, cogs, and clockwork motifs, along with Victorian attire reimagined with a mechanical twist. The color palette leans toward rich browns, coppers, and metallic hues, evoking the vintage charm of a bygone era. Steampunk designs have a whimsical and adventurous appeal, resonating with those who appreciate the fusion of history, fantasy, and innovation.

10. Grunge

Emerging in the 1990s as a reaction against mainstream fashion, grunge style embraces a rugged, unpolished look. T-shirts designed in the grunge style often feature distressed textures, flannel patterns, and rebellious messages. The color palette is dark and moody, with black, gray, and earthy tones dominating the designs. Grunge-inspired t-shirts evoke a sense of authenticity and anti-establishment sentiment, appealing to those who embrace a carefree and rebellious spirit in their fashion choices.

11. Vaporwave

A contemporary take on vintage aesthetics, vaporwave style combines retro imagery with futuristic elements, pastel colors, and glitch effects. T-shirts designed in the vaporwave style often feature pixelated graphics, 1980s and 1990s references, and a dreamy, surreal atmosphere. The color palette includes soft pastels, neon hues, and iridescent shades, creating a nostalgic yet otherworldly vibe. Vaporwave designs resonate with those who appreciate the blending of past and future, offering a captivating visual journey into a retro-futuristic realm.

Vintage Design Tips

- Pick one era and stick with it. This will give your designs thematic coherence.

- Use typical colors from the era of your choice. Whatever option you go for, check out actual designs from that period to see what palette was commonly used at the time and find that authentic feel. For inspiration, check out articles like this vintage color palette, and if you need a little help with your color theory, we’ve put together a run-down of the best tools for thinking about color.

- Make sure you match your font to your period, too. Different typography is appropriate for different eras.

- To make it simple, break down your design into its constituent elements and construct each one according to the design principles of the era you are working with.

- Don’t overdo it. Yu design still needs to appeal to a contemporary audience; if that means sacrificing some authenticity to stay within the design norms and expectations of modern audiences, so be it.

Note: there’s a fine line between vintage and outdated. To keep your designs looking relevant and fresh, carefully mix elements of vintage style with modern design features. It’s a balancing act, so don’t be scared to experiment!

Resources and tutorials

- Vintage design tips from 99 Designs

- Vintage poster design with Kreafolk

- Ultimate vintage poster design from Kittl

- Vintage T-shirt design in Photoshop with Spoongraphics

- Vintage logo design in illustrator from Spoongraphics

- Vintage large letter postcard design from Spoongraphics

Still feeling the twangs of nostalgia? Check out our guide to design styles of the 90s. Happy creating!

The post In-Depth Guide to Vintage Design appeared first on The US Spreadshirt Blog.

Looking for cool gifts? Check Rott515 store!

Branding yourself as a designer

Four steps for building our personal brands.

“As an immigrant woman in [design and] tech, I feel like I might have hit a ceiling in terms of building a personal brand.”

One of the readers of my newsletter reached out to me, replying to the piece I wrote recently about starting a company as a creative, in which I shared several pieces of advice from my industry friends/colleagues. While pondering about going out on my own, I received advice from Brett Lovelady, the founder of Astro Studios in the US and an industrial designer extraordinaire.

“Build your brand” was the advice.

The reader continued:

“I speak at conferences, write a Substack, mentor accelerator programs, and more… but I can’t seem to break through to get a meaningful media feature. FastCo, Wired, Forbes, TechCrunch, etc. seems like all of that is guard railed for executives of big companies, those willing to shill $2,500 to be a part of the paid council, and people with a giant influential network. Is the only way to get your thoughts out through hiring a PR person? Do you happen to have any advice for someone like me?”

When thinking about this reader’s question, the analog that came to mind was Marie Kondo, a Japanese organizing consultant also known as KonMari, author, and most famous for her Netflix series “Tidying Up with Marie Kondo.”

While there are thousands of well-known individuals from whom we could take cues and an endless list of how-to’s on building your personal brand, how Kondo built her own provides us designers with useful hints. She turned a mundane and intangible act of tidying up into a tangible profession and built her brand.

There are four steps Kondo went through that are parallel to how we can think about and elevate what we do as designers.

1. Relevance

To start off with, everyone wants a clean, tidy home or office. The need is obvious and what she offers is immediately relevant. However, that could easily be relegated to a cleaning service. There is a limit to how much one can charge for a cleaning service. At the danger of sounding like an elite, this occupation becomes a race to the bottom.

In design, there are plenty of designers and cheap services out there that would give the customer, say, a logo for a few hundred dollars or even for free. Services like Canva and Wix provide non-designers tools to design logos on their own. Not only can competing on price when providing a design service become a race to the bottom, but it’s also a race to irrelevance.

As a child, Kondo says she would look at her mother’s magazines about home organization and become interested in tidying up. During her college days, whenever she visited her friends’ apartments and saw some messiness, she would offer to tidy up. Also, while doing secretarial work to make some extra cash, she happened to notice a very messy desk of a manager. One day she offered to tidy his desk up.

Sounds a little OCD. But that’s a prerequisite for us designers.

The good news about this kind of service is that it could be a recurring business as no room stays clean and we could generate repeat customers. But this is where she found an insight that eventually became the crux of what she would be known for and around which she built a personal brand.

While she started getting paid for her cleaning services that she could repeat, she pivoted to teaching her customers how to tidy up and organize better so that their homes and offices would stay tidy.

An obvious insight here is “everyone wants a tidy home/office.” But a more relevant insight is “everyone wants a tidy home/office that stays tidy. “

Instead of becoming just another cleaning service provider, she positioned herself as an organizational consultant. Rather than racing to the bottom, she started to elevate her service to a higher level.

2. Differentiation

In addition to her insight, Kondo had a peculiar way of organizing. She would hold each item to her heart to see if it would spark joy, which she later turned into the Method. Many people take joy in having a clean home/office but she may be the first person to turn tidying up into a method by looking for joy in items she and her customers owned. Quite unique indeed.

But the KonMari Method wasn’t born overnight.

While working as an office worker and after she started to consult on the side as a hobby, she decided to attend a book writing course at her friend’s suggestion. That led to the eventual publication of her international bestselling book “The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up” in which she methodically described her rules of organizing. “Ask Yourself If It Sparks Joy” is Rule №6 of her six-rule method.

Now, there are a few elements to her success that made her an international phenomenon.

First, a different idea. Tidying up isn’t all that desirable as an idea, but a life-changing magic of tidying up sounds intriguing. Not everyone wants to tidy up but if tidying up could change our lives, wouldn’t we all want that magic?

Asking an object if it sparks joy and then thanking it is admittedly quirky and even a little weird but that did differentiate Kondo. I emphasize “different” here. Anyone can have an idea, some can have better ideas. Coming up with different ideas is the hard part.

As designers, we need to relentlessly pursue ideas that are different, not just better.

Second, articulation. The crucial step she took was articulating and documenting her way of tidying up. It’s one thing to have ways of doing things in our heads but once we verbalize and document, those ways become more concrete and tangible.

More importantly, it’s the way she articulated it. A book titled “A Better Way of Tidying Up” might make some people curious, but “The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up” is much more imaginative and inspiring.

In addition to her articulation of her method being unique, the translation is absolutely genius. Each language has its nuance and peculiarity that often gets lost in translation. “Spark joy” is actually not the translation of the original Japanese version of “ tokimeki.” If you look up this word in a dictionary, it provides several awkward translations. Combining “spark” and “joy” to convey the meaning of tokimeki was a brilliant touch of the translator.

This leads to my third point: naming. Kondo happened to have a name that was easy to pronounce for non-Japanese speakers. Kondo’s first name Marie is actually pronounced “Ma-Ri-Eh” but to the English speakers, it just looks like the Western name Marie and is easy to pronounce, and her nickname KonMari is equally so.

It’s quite common in Japanese to conjugate the first few letters of first and last names to give shorter nicknames not just to people but services or brands. KonMari was a nickname her friends gave by combining Kondo and Marie and shortening it. Starbucks, for instance, in Japanese becomes “ Sutaba” and Don Quijote, a massively successful discount store in Japan, becomes “ Donki. “

Not only was her method of finding what sparks joy when tidying up unique and differentiated, but it was also unexpectedly simple and easy to remember, both conceptually and phonetically. The fact that the KonMari method would be easy to pronounce for foreigners may not have been intentional but it later made a big difference for her personal brand especially outside of Japan.

Naming our ideas in a simple, memorable way can go a surprisingly long way.

3. Presentation

Once she elevated what could have been a run-of-the-mill cleaning service and organizational consultation to a new level, she paid attention to how she presented herself.

She dressed in a reserved outfit that would exude a clean image and carried a hairstyle that was tidy and distinctive but not overstated. She herself became the expression of her ideology and established an easily recognizable visual presentation.

Dressing a certain way or having a distinct visual style is a common, tried-and-tested trick in the entertainment world but isn’t rare in the corporate world. In modern times, Steve Jobs is the top example of someone who dressed one way and one way only with a pair of John Lenon-inspired round glasses that added to his signature look. This was perhaps a conscious jab at his nemesis Bill Gates who had a more nerdy style. The disgraced Elizabeth Holmes is another person in a more recent memory who manufactured not only her image but also her peculiar low-pitched voice and achieved enormous brand recognition. She knew what she was doing as she later changed her appearance during her trial for fraud to distance herself from her previous personal brand. It didn’t quite work this time.

In the design sphere, we can also spot individuals who have established particular ways of presenting themselves. In addition to consistently producing beautiful products, a closely trimmed head, a soft-spoken British accent, and a T-shirt are elements that made Jonathan Ive, the long-time design collaborator of Steve Jobs and the former head of design, the most well-known, iconic designer of our time. After Ive, can we name another designer from Apple? I didn’t think so.

A visual presentation of oneself is just a clean and consistent punctuation of a sentence. Needless to say, what’s critical is the idea or the piece of innovation. When that is made visible, it can be exponentially more powerful.

Tinker Hatfield, a legendary sneaker designer who is credited with designing some of the most famous consumer products in modern history, was phenomenally skilled at visually presenting innovation. Nike Air, a shock-absorption technology in running shoes, was designed in the 1980s by Hatfield and his team and has been one of the most successful product brands. The idea of cushioning so soft it’s like running on air is immediately visible in its design AND is easily understood. It telegraphically presents and tells us what it is and does for us.

4. Consistency

One can gain recognition overnight but overnight recognition doesn’t build a personal brand.

Kondo became a well-known figure in her 20s in Japan first. Now, for over a decade, she has maintained her consistent presentation. As long as she’s been practicing as a professional organizational consultant well before she became an international figure, she had her look. She must have had an urge to change her hairstyle but I praise her dedication to her personal brand.

Karl Lagerfeld, Rei Kawakubo, and Yoji Yamamoto are some of the most iconic design figures with specific visual presentations of themselves that many of us recognize. Hairstyles, glasses, accessories, and outfits are all elements that can build personal brands beyond the products or things we as designers become known for.

However, it must be emphasized that these visual elements and styles are merely a cherry on top. We must first be known for what we do and do it consistently, not how we appear.

In Kondo’s case, she established a narrative around organizing and sparking joy, and she’s been very consistent in that narrative.

More recently, though, she admits that, as a mother of young children, keeping her house tidy is no longer her priority. But that doesn’t mean she is parting ways with her brand. She started to expand the idea of sparking joy into relationship consultation and maintaining her consistency.

Nothing stays relevant forever so we must find ways to evolve. While it’s important for us to keep up with the change around us, it’s also important to have certain ideas and philosophies that we can keep consistent. There is a fine balance we have to keep looking for between relevance and consistency.

To answer the original question from the reader:

“I can’t seem to break through to get a meaningful media feature. Is the only way to get your thoughts out through hiring a PR person?”

A media feature is nice but I would encourage you to ask yourself the following:

- Relevance: Is my service relevant to my clients?

- Differentiation:How is my service different from others?

- Presentation:How am I presenting my service and myself?